牛津临床医学手册(第十版)英文原版.pdf

http://www.100md.com

2020年11月17日

英文原版_1.jpg) |

| 第1页 |

英文原版_2.jpg) |

| 第7页 |

英文原版_3.jpg) |

| 第13页 |

英文原版_4.jpg) |

| 第26页 |

英文原版_5.jpg) |

| 第49页 |

英文原版_6.jpg) |

| 第820页 |

参见附件(46721KB,908页)。

牛津临床医学手册(第十版)英文原版

牛津临床医学手册是医学文献中独一无二的,它是医学核心领域的完整而简明的指南,也鼓励从患者的角度思考世界,提供全面的,以患者为中心的方法,小编今天给大家带来了牛津临床医学手册(第十版)英文原版,有需要的就快来吧

相关内容部分预览

内容简介

艾滋病的大流行已加快步伐;糖尿病患者正在倍增;全球变暖使新的疾病进入居民免疫力差的地区——这些效应在第9章和第14章描述;面临病原体进化,曾经值得信赖的抗生素变得无效;航空正将全新的疾病(如SARS)扩散到全球;医源性疾病从未像现在这样常见……

更多的变化包括:基本药物的小部分;临床技能的新部分;更多的心电图内容;很多反映当前实践的新方法——如从包容一切(以患者为中心的护理)到罕见的细节

(比如多发性内分泌腺瘤综合征表现的不同形式及其基因联系)的新主题。有新的记忆法——通常不会太烦人,不会太粗糙。很多重新组合是循证的(例如糖尿病)。

但是最重要的变化是最难的部分——书中大量的微小变化。知识渐进性的更新会像珊瑚一样积累,从而呈现出新的面貌。

目录

第1章 医学思考

第2章 流行病学

第3章 临床技能

第4章 症状和体征

第5章 心血管疾病

第6章 胸部疾病

第7章 胃肠病学

第8章 肾脏病学

第9章 内分泌学

第10章 神经病学

第11章 风湿病学

第12章 肿瘤学

第13章 外科学

第14章 感染性疾病

第15章 血液病学

第16章 临床生物化学

第17章 参考值范围

第18章 以人名命名的综合征

第19章 操作规程

第20章 急诊

牛津临床医学手册(第十版)英文原版截图

Acute abdomen 606

Acute kidney injury 298

Addisonian crisis 836

Anaphylaxis 794

Aneurysm, abdominal aortic 654

intracranialextradural 78, 482

gastrointestinal 256, 820

rectal 629

variceal 257, 820

Antidotes, poisoning 842

Arrhythmias, broad complex 128, 804

narrow complex, SVT 126, 806

Asthma 810

Asystole 895

Atrial ? utter? brillation

Bacterial shock 790

Blast injury 851

Bradycardia 124

Burns 846

Cardiac arrest 894 (Fig A3)

Cardiogenic tamponade 802

Cardioversion, DC 770

Central line insertion (CVP line) 774

Cerebral oedema 830

Chest drain 766

Coma 786

Cricothyrotomy 772

Cyanosis 186–9

Cut-down 761

De? brillation 770, 894 (Fig A3)

Diabetes emergencies 832–4

Disseminated intravascular coagulopathy

(DIC) 352

Disaster, major 850

Encephalitis 824

Epilepsy, status 826

Extradural haemorrhage 482

Fluids, IV 666, 790

Haematemesis 256–7

Haemorrhage 790

Hyperthermia 790, 838

Hypoglycaemia 214, 834

Hypothermia 848

Intracranial pressure, raised 830

Ischaemic limb 656

Malaria 416

Malignant hyperpyrexia 572

Index to emergency topics

‘Don’t go so fast: we’re in a hurry!’—Talleyrand to his coachman.

Malignant hypertension 140

Meningitis 822

Meningococcaemia 822

Myocardial infarction 796

Needle pericardiocentesis 773

Neutropenic sepsis 352

Obstructive uropathy 641

Oncological emergencies 528

Opioid poisoning 842

Overdose 838–44

Pacemaker, temporary 776

Pericardiocentesis 773

Phaeochromocytoma 837

Pneumonia 816

Pneumothorax 814

Poisoning 838–44

Potassium, hyperkalaemia 674

hypokalaemia 674

Pulmonary embolism 818

Respiratory arrest 894 (Fig A3)

Respiratory failure 188

Resuscitation 894 (Fig A3)

Rheumatological emergencies 538

Shock 790

Smoke inhalation 847

Sodium, hypernatraemia 672

hyponatraemia 672

Spinal cord compression 466, 543

Status asthmaticus 810

Status epilepticus 826

Stroke 470

Superior vena cava obstruction 528

Supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) 806

Testicular torsion 652

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura

(TTP) 315

Thyroid storm 834

Transfusion reaction 349

Varices, bleeding 257, 820

Vasculitis, acute systemic 556

Venous thromboembolism, leg 656

pulmonary 818

Ventricular arrhythmias 128, 804

Ventricular failure, left 800

Ventricular ? brillation 894 (Fig A3)

Ventricular tachycardia 128, 804

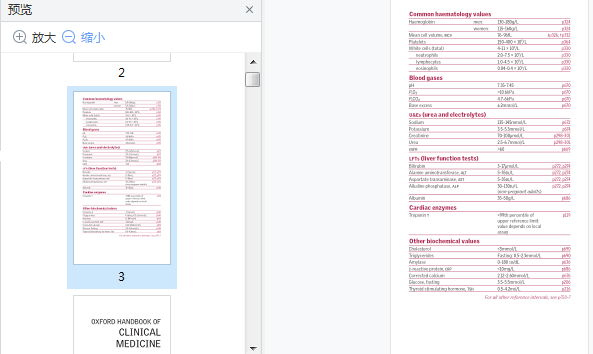

_OHCM_10e.indb b _OHCM_10e.indb b 02052017 19:06 02052017 19:06Common haematology values

Haemoglobin men: 130–180gL p324

women: 115–160gL p324

Mean cell volume, MCV 76–96fL p326; p332

Platelets 150–400 ≈ 109

L p364

White cells (total) 4–11 ≈ 109

L p330

neutrophils 2.0–7.5 ≈ 109

L p330

lymphocytes 1.0–4.5 ≈ 109

L p330

eosinophils 0.04–0.4 ≈ 109

L p330

Blood gases

pH 7.35–7.45 p670

PaO2 >10.6kPa p670

PaCO2 4.7–6kPa p670

Base excess ± 2mmolL p670

UES (urea and electrolytes)

Sodium 135–145mmolL p672

Potassium 3.5–5.3mmolL p674

Creatinine 70–100μmolL p298–301

Urea 2.5–6.7mmolL p298–301

eGFR >60 p669

LFTS (liver function tests)

Bilirubin 3–17μmolL p272, p274

Alanine aminotransferase, ALT 5–35IUL p272, p274

Aspartate transaminase, AST 5–35IUL p272, p274

Alkaline phosphatase, ALP 30–130IUL

(non-pregnant adults)

p272, p274

Albumin 35–50gL p686

Cardiac enzymes

Troponin T <99th percentile of

upper reference limit:

value depends on local

assay

p119

Other biochemical values

Cholesterol <5mmolL p690

Triglycerides Fasting: 0.5–2.3mmolL p690

Amylase 0–180 IUdL p636

C-reactive protein, CRP <10mgL p686

Corrected calcium 2.12–2.60mmolL p676

Glucose, fasting 3.5–5.5mmolL p206

Thyroid stimulating hormone, TSH 0.5–4.2mUL p216

For all other reference intervals, see p750–7

_OHCM_10e.indb c _OHCM_10e.indb c 02052017 19:06 02052017 19:06OXFORD HANDBOOK OF

CLINICAL

MEDICINE

TENTH EDITION

Ian B. Wilkinson

Tim Raine

Kate Wiles

Anna Goodhart

Catriona Hall

Harriet O’Neill

3 _OHCM_10e.indb i _OHCM_10e.indb i 02052017 19:06 02052017 19:06Contents

Each chapter’s contents are detailed on its ? rst page

Prefaces to the ? rst and tenth editions iv

Acknowledgements v

Symbols and abbreviations vi

1 Thinking about medicine 0

2 History and examination 24

3 Cardiovascular medicine 92

4 Chest medicine 160

5 Endocrinology 202

6 Gastroenterology 242

7 Renal medicine 292

8 Haematology 322

9 Infectious diseases 378

10 Neurology 444

11 Oncology and palliative care 518

12 Rheumatology 538

13 Surgery 564

14 Clinical chemistry 662

15 Eponymous syndromes 694

16 Radiology 718

17 Reference intervals, etc. 750

18 Practical procedures 758

19 Emergencies 778

20 References 852

Index 868

Early warning score 892

Cardiac arrest 894

_OHCM_10e.indb iii _OHCM_10e.indb iii 02052017 19:06 02052017 19:06Preface to the tenth edition

This is the ? rst edition of the book without either of the original authors—Tony Hope

and Murray Longmore. Both have now moved on to do other things, and enjoy a

well-earned rest from authorship. In this book, I am joined by a Nephrologist, Gas-

troenterologist, and trainees destined for careers in Cardiology, Dermatology, and

General Practice. Five physicians, each with very dif erent interests and approaches,yet bringing their own knowledge, expertise, and styles. When combined with that

of our specialist and junior readers, I hope this creates a book that is greater than

the sum of its parts, yet true to the original concept and ethos of the original authors.

Life and medicine have moved on in the 30 years since the ? rst edition was published,but medicine and science are largely iterative; true novel ‘ground-breaking’ or ‘prac-

tice-changing’ discoveries are rare, to quote Isaac Newton: ‘If I have seen further, it

is by standing on the shoulders of giants’. Therefore, when we set about writing this

edition we drew inspiration from the original book and its authors; updating, adding,and clarifying, but trying to retain the unique feel and perspective that the OHCM has

provided to generations of trainees and clinicians.

IBW, 2017

We wrote this book not because we know so much, but because we know we

remember so little…the problem is not simply the quantity of information, but the

diversity of places from which it is dispensed. Trailing eagerly behind the surgeon,the student is admonished never to forget alcohol withdrawal as a cause of post-

operative confusion. The scrap of paper on which this is written spends a month

in the pocket before being lost for ever in the laundry. At dif erent times, and in

inconvenient places, a number of other causes may be presented to the student.

Not only are these causes and aphorisms never brought together, but when, as a

surgical house oi cer, the former student faces a confused patient, none is to hand.

We aim to encourage the doctor to enjoy his patients: in doing so we believe he

will prosper in the practice of medicine. For a long time now, house oi cers have

been encouraged to adopt monstrous proportions in order to straddle the diverse

pinnacles of clinical science and clinical experience. We hope that this book will

make this endeavour a little easier by moving a cumulative memory burden from

the mind into the pocket, and by removing some of the fears that are naturally felt

when starting a career in medicine, thereby freely allowing the doctor’s clinical

acumen to grow by the slow accretion of many, many days and nights.

RA Hope and JM Longmore, 1985

Preface to the ? rst edition

_OHCM_10e.indb iv _OHCM_10e.indb iv 02052017 19:06 02052017 19:06Symbols and abbreviations

..........this fact or idea is important

.......don’t dawdle!—prompt action saves lives

1 ...........reference

:......male-to-female ratio. :=2:1 means twice as

common in males

.........therefore

~ ..........approximately

–ve ......negative (+ve is positive)

........ increased or decreased

.......normal (eg serum level)

1° ........primary

2° ........secondary

..........diagnosis

........dif erential diagnosis

A:CR ......albumin to creatinine ratio (mgmmol)

A2 .........aortic component of the 2nd heart sound

Ab ......antibody

ABC ......airway, breathing, and circulation

ABG .....arterial blood gas: PaO2, PaCO2, pH, HCO3

ABPA ....allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis

ACE-i .....angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor

ACS .......acute coronary syndrome

ACTH ....adrenocorticotrophic hormone

ADH .....antidiuretic hormone

AF ........atrial ? brillation

AFB ......acid-fast bacillus

Ag .......antigen

AIDS ....acquired immunode? ciency syndrome

AKI ........acute kidney injury

ALL ......acute lymphoblastic leukaemia

ALP ......alkaline phosphatase

AMA ....antimitochondrial antibody

AMP .....adenosine monophosphate

ANA .....antinuclear antibody

ANCA ...antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody

APTT ....activated partial thromboplastin time

AR ........aortic regurgitation

ARB .....angiotensin II receptor ‘blocker’ (antagonist)

ARDS ...acute respiratory distress syndrome

ART ......antiretroviral therapy

AS ........aortic stenosis

ASD .....atrial septal defect

AST ......aspartate transaminase

ATN ......acute tubular necrosis

ATP ......adenosine triphosphate

AV ........atrioventricular

AVM .....arteriovenous malformation(s)

AXR .....abdominal X-ray (plain)

Ba ........barium

BAL ......bronchoalveolar lavage

bd .......bis die (Latin for twice a day)

BKA .....below-knee amputation

BNF ......British National Formulary

BNP ......brain natriuretic peptide

BP ........blood pressure

BPH ......benign prostatic hyperplasia

bpm ....beats per minute

ca ........cancer

CABG ...coronary artery bypass graft

cAMP ...cyclic adenosine monophosphate (AMP)

CAPD ...continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis

CCF ......congestive cardiac failure (ie left and right heart

failure)

CCU ......coronary care unit

CDT ......Clostridium dif? cile toxin

CHB ......complete heart block

CHD ......coronary heart disease

CI .........contraindications

CK ........creatine (phospho)kinase

CKD ......chronic kidney disease

CLL ......chronic lymphocytic leukaemia

CML .....chronic myeloid leukaemia

CMV .....cytomegalovirus

CNS ......central nervous system

COC ......combined oral contraceptive pill

COPD ....chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

CPAP ....continuous positive airway pressure

CPR ......cardiopulmonary resuscitation

CRP ......c-reactive protein

CSF ......cerebrospinal ? uid

CT ........computed tomography

CVA ......cerebrovascular accident

CVP ......central venous pressure

CVS ......cardiovascular system

CXR ......chest x-ray

d ..........day(s); also expressed as 7; months are 12

DC ........direct current

DIC ......disseminated intravascular coagulation

DIP ......distal interphalangeal

dL .......decilitre

DM .......diabetes mellitus

DOAC ...direct oral anticoagulant

DU ........duodenal ulcer

DV .....diarrhoea and vomiting

DVT ......deep venous thrombosis

DXT ......deep radiotherapy

EBV ......Epstein–Barr virus

ECG ......electrocardiogram

Echo ...echocardiogram

EDTA ....ethylene diamine tetra-acetic acid (anticoagulant

coating, eg in FBC bottles)

EEG ......electroencephalogram

eGFR ....estimated glomerular ? ltration rate (in mL

min1.73m2)

ELISA ...enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

EM .......electron microscope

EMG .....electromyogram

ENT ......ear, nose, and throat

ERCP ....endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

ESR ......erythrocyte sedimentation rate

ESRF ....end-stage renal failure

EUA ......examination under anaesthesia

FBC ......full blood count

FDP ......? brin degradation products

FEV1 .....forced expiratory volume in 1st sec

FiO2 ....partial pressure of O2 in inspired air

FFP ......fresh frozen plasma

FSH ......follicle-stimulating hormone

FVC ......forced vital capacity

g ..........gram

G6PD ....glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase

GA .......general anaesthetic

GCS ......Glasgow Coma Scale

GFR ......glomerular ? ltration rate

GGT ......gamma-glutamyl transferase

GH ........growth hormone

GI ........gastrointestinal

GN ........glomerulonephritis

GP ........general practitioner

GPA ......granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly

Wegener’s granulomatosis)

GTN ......glyceryl trinitrate

GTT ......glucose tolerance test

GU(M) ..genitourinary (medicine)

h ..........hour

HAV .....hepatitis A virus

Hb .......haemoglobin

HbA1c .glycated haemoglobin

HBSAg ..hepatitis B surface antigen

HBV .....hepatitis B virus

HCC ......hepatocellular cancer

HCM .....hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy

Hct ......haematocrit

HCV ......hepatitis C virus

HDV .....hepatitis D virus

HDL ......high-density lipoprotein

HHT ......hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia

HIV ......human immunode? ciency virus

HLA ......human leucocyte antigen

HONK ...hyperosmolar non-ketotic (coma)

HPV ......human papillomavirus

HRT ......hormone replacement therapy

HSP ......Henoch–Sch?nlein purpura

HSV ......herpes simplex virus

HUS ......haemolytic uraemic syndrome

IBD ...... in? ammatory bowel disease

IBW ..... ideal body weight

ICD ...... implantable cardiac de? brillator

ICP ....... intracranial pressure

IC(T)U .. intensive care unit

IDDM ... insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus

IFN- .. interferon alpha

IE ......... infective endocarditis

Ig ........ immunoglobulin

IHD ...... ischaemic heart disease

IM ........ intramuscular

INR ...... international normalized ratio

IP ......... interphalangeal

IPPV .... intermittent positive pressure ventilation

ITP ....... idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura

IU ........ international unit

IVC ...... inferior vena cava

IV(I) .... intravenous (infusion)

IVU ...... intravenous urography

JVP ...... jugular venous pressure

K ..........potassium

kg .......kilogram

KPa ......kiloPascal

L .......... litre

LAD ........left axis deviation on the ECG

LBBB .... left bundle branch block

LDH ...... lactate dehydrogenase

LDL ...... low-density lipoprotein

LFT ...... liver function test

_OHCM_10e.indb vi _OHCM_10e.indb vi 02052017 19:06 02052017 19:06LH ........ luteinizing hormone

LIF ....... left iliac fossa

LKKS .... liver, kidney (R), kidney (L), spleen

LMN ..... lower motor neuron

LMWH .. low-molecular-weight heparin

LOC ...... loss of consciousness

LP ........ lumbar puncture

LUQ ...... left upper quadrant

LV ........ left ventricle of the heart

LVF ....... left ventricular failure

LVH ...... left ventricular hypertrophy

MAI .....Mycobacterium avium intracellulare

MALT ...mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue

mane ..morning (from Latin)

MAOI ...monoamine oxidase inhibitor

MAP .....mean arterial pressure

MCS ...microscopy, culture, and sensitivity

mcg ....microgram

MCP .....metacarpo-phalangeal

MCV .....mean cell volume

MDMA ..3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine

ME .......myalgic encephalomyelitis

mg ......milligram

MI ........myocardial infarction

min(s) minute(s)

mL .......millilitre

mmHg millimetres of mercury

MND .....motor neuron disease

MR .......modi? ed release or mitral regurgitation

MRCP ...magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography

MRI ......magnetic resonance imaging

MRSA ...meticillin-resistant Staph. aureus

MS .......multiple sclerosis

MSM ....men who have sex with men

MSU .....midstream urine

NV .....nausea andor vomiting

NAD .....nothing abnormal detected

NBM .....nil by mouth

ND ........noti? able disease

NEWS ..National Early Warning Score

ng .......nanogram

NG ........nasogastric

NHS .....National Health Service (UK)

NICE ....National Institute for Health and Care Excellence,http:www.nice.org.uk

NIDDM .non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus

NMDA ..N-methyl-D-aspartate

NNT .....number needed to treat

nocte ..at night

NR ........normal range (=reference interval)

NSAID ..non-steroidal anti-in? ammatory drug

OCP ......oral contraceptive pill

od .......omni die (Latin for once daily)

OGD .....oesophagogastroduodenoscopy

OGTT ....oral glucose tolerance test

OHCS ....Oxford Handbook of Clinical Specialties

om ......omni mane (in the morning)

on .......omni nocte (at night)

OPD ......outpatients department

OT ........occupational therapist

P:CR .....protein to creatinine ratio (mgmmol)

P2 .........pulmonary component of 2nd heart sound

PaCO2 ...partial pressure of CO2 in arterial blood

PAN ......polyarteritis nodosa

PaO2 .....partial pressure of O2 in arterial blood

PBC ......primary biliary cirrhosis

PCR ......polymerase chain reaction

PCV ......packed cell volume

PE ........pulmonary embolism

PEEP ....positive end-expiratory pressure

PEF(R) ..peak expiratory ? ow (rate)

PERLA ..pupils equal and reactive to light and

accommodation

PET ......positron emission tomography

PID ......pelvic in? ammatory disease

PIP .......proximal interphalangeal (joint)

PMH .....past medical history

PND .....paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea

PO ........per os (by mouth)

PPI .......proton pump inhibitor, eg omeprazole

PR ........per rectum (by the rectum)

PRL ......prolactin

PRN ......pro re nata (Latin for as required)

PRV ......polycythaemia rubra vera

PSA ......prostate-speci? c antigen

PTH ......parathyroid hormone

PTT ......prothrombin time

PUO ......pyrexia of unknown origin

PV ........per vaginam (by the vagina, eg pessary)

PVD ......peripheral vascular disease

QDS ......quater die sumendus; take 4 times daily

qqh .....quarta quaque hora: take every 4h

R ..........right

RA ........rheumatoid arthritis

RAD .....right axis deviation on the ECG

RBBB ...right bundle branch block

RBC ......red blood cell

RCT ......randomized controlled trial

RDW ....red cell distribution width

RFT ......respiratory function tests

Rh ........Rhesus status

RIF .......right iliac fossa

RRT ......renal replacement therapy

RUQ .....right upper quadrant

RV ........right ventricle of heart

RVF ......right ventricular failure

RVH ......right ventricular hypertrophy

.........recipe (Latin for treat with)

ssec ...second(s)

S1, S2 ....? rst and second heart sounds

SBE ......subacute bacterial endocarditis

SC ........subcutaneous

SD ........standard deviation

SE ........side-ef ect(s)

SIADH ..syndrome of inappropriate anti-diuretic hormone

secretion

SL ........sublingual

SLE ......systemic lupus erythematosus

SOB ......short of breath

SOBOE .short of breath on exertion

SpO2 ....peripheral oxygen saturation (%)

SR ........slow-release

Stat ....statim (immediately; as initial dose)

STDI ...sexually transmitted diseaseinfection

SVC ......superior vena cava

SVT ......supraventricular tachycardia

T° .........temperature

t? ........biological half-life

T3 ........tri-iodothyronine

T4 ........thyroxine

TB ........tuberculosis

TDS ......ter die sumendus (take 3 times a day)

TFT ......thyroid function test (eg TSH)

TIA ......transient ischaemic attack

TIBC ....total iron-binding capacity

TPN ......total parenteral nutrition

TPR ......temperature, pulse, and respirations count

TRH ......thyrotropin-releasing hormone

TSH ......thyroid-stimulating hormone

TTP ......thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura

U ..........units

UC ........ulcerative colitis

UE .....urea and electrolytes and creatinine

UMN .....upper motor neuron

URT(I) ..upper respiratory tract (infection)

US(S) ....ultrasound (scan)

UTI ......urinary tract infection

VDRL ....Venereal Diseases Research Laboratory

VE ........ventricular extrasystole

VF ........ventricular ? brillation

VHF ......viral haemorrahgic fever

VMA ....vanillylmandelic acid (HMMA)

VQ .......ventilationperfusion scan

VRE ......vancomycin resistant enterococci

VSD ......ventricular-septal defect

VT ........ventricular tachycardia

VTE ......venous thromboembolism

WBC ....white blood cell

WCC ....white blood cell count

wk(s) ..week(s)

yr(s) ...year(s)

ZN ........Ziehl–Neelsen stain, eg for mycobacteria

_OHCM_10e.indb vii _OHCM_10e.indb vii 02052017 19:06 02052017 19:06_OHCM_10e.indb viii _OHCM_10e.indb viii 02052017 19:06 02052017 19:06‘He who studies medicine without books sails an unchartered sea, but he who

studies medicine without patients does not go to sea at all’

William Osler 1849–1919

The word ‘patient’ occurs frequently throughout this book.

Do not skim over it lightly.

Rather pause and dof your metaphorical cap, of ering due respect to those

who by the opening up of their lives to you, become your true teachers.

Without your patients, you are a technician with a useless skill.

With them, you are a doctor.

_OHCM_10e.indb ix _OHCM_10e.indb ix 02052017 19:06 02052017 19:061 Thinking about medicine

Contents

The Hippocratic oath 1

Medical care 2

Compassion 3

The diagnostic puzzle 4

Being wrong 5

Duty of candour 5

Bedside manner and communication

skills 6

Prescribing drugs 8

Surviving life on the wards 10

Death 12

Medical ethics 14

Psychiatry on medical and surgical

wards 15

The older person 16

The pregnant woman 17

Epidemiology 18

Randomized controlled trials 19

Medical mathematics 20

Evidence-based medicine (EBM) 22

Medicalization 23

Fig 1.1 Asclepius, the god of healing and his three

daughters, Meditrina (medicine), Hygieia (hy-

giene), and Panacea (healing). The staf and single

snake of Asclepius should not be confused with

the twin snakes and caduceus of Hermes, the dei-

· ed trickster and god of commerce, who is viewed

with disdain.

Plate from Aubin L Millin, Galerie Mythologique (1811)

We thank Dr Kate Mans? eld, our Specialist Reader, for her contribution to this chapter.

_OHCM_10e.indb x _OHCM_10e.indb x 02052017 19:06 02052017 19:06Thinking about medicine

1 The Hippocratic oath ~4th century BC

I

swear by Apollo the physician and Asclepius and Hygieia and Panacea and all the

gods and goddesses, making them my witnesses, that I will ful? l according to my

ability and judgement this oath and this covenant.

T

o hold him who has taught me this art as equal to my parents and to live my

life in partnership with him, and if he is in need of money to give him a share of

mine, and to regard his of spring as equal to my own brethren and to teach them

this art, if they desire to learn it, without fee and covenant. I will impart it by pre-

cept, by lecture and by all other manner of teaching, not only to my own sons but

also to the sons of him who has taught me, and to disciples bound by covenant and

oath according to the law of physicians, but to none other.

T

he regimen I shall adopt shall be to the bene? t of the patients to the best of

my power and judgement, not for their injury or any wrongful purpose.

I

will not give a deadly drug to anyone though it be asked of me, nor will I lead

the way in such counsel.

1

And likewise I will not give a woman a pessary to pro-

cure abortion.

2

But I will keep my life and my art in purity and holiness. I will not

use the knife,3

not even, verily, on suf erers of stone but I will give place to such as

are craftsmen therein.

Whatsoever house I enter, I will enter for the bene? t of the sick, refraining

from all voluntary wrongdoing and corruption, especially seduction of male

or female, bond or free.

Whatsoever things I see or hear concerning the life of men, in my attend-

ance on the sick, or even apart from my attendance, which ought not to

be blabbed abroad, I will keep silence on them, counting such things to be as reli-

gious secrets.

I

f I ful? l this oath and do not violate it, may it be granted to me to enjoy life and

art alike, with good repute for all time to come; but may the contrary befall me

if I transgress and violate my oath.

Paternalistic, irrelevant, inadequate, and possibly plagiarized from the followers of

Pythagoras of Samos; it is argued that the Hippocratic oath has failed to evolve

into anything more than a right of passage for physicians. Is it adequate to address

the scienti? c, political, social, and economic realities that exist for doctors today?

Certainly, medical training without a fee appears to have been con? ned to history.

Yet it remains one of the oldest binding documents in history and its principles of

commitment, ethics, justice, professionalism, and con? dentiality transcend time.

The absence of autonomy as a fundamental tenet of modern medical care can

be debated. But just as anatomy and physiology have been added to the doctor’s

repertoire since Hippocrates, omissions should not undermine the oath as a para-

digm of self-regulation amongst a group of specialists committed to an ideal. And

do not forget that illness may represent a temporary loss of autonomy caused by

fear, vulnerability, and a subjective weighting of present versus future. It could

be argued that Hippocratic paternalism is, in fact, required to restore autonomy.

Contemporary versions of the oath often fail to make doctors accountable for

keeping to any aspect of the pledge. And beware the oath that is nothing more

than historic ritual without accountability, for then it can be superseded by per-

sonal, political, social, or economic priorities:

‘In Auschwitz, doctors presided over the murder of most of the one million

victims…. [They] did not recall being especially aware in Auschwitz of their

Hippocratic oath, and were not surprisingly, uncomfortable discussing it…The

oath of loyalty to Hitler…was much more real to them.’

Robert Jay Lifton, The Nazi Doctors.

The endurance of the Hippocratic oath

1 This is unlikely to be a commentary on euthanasia (easeful death) as the oath predates the word. Rather,it is believed to allude to the common practice of using doctors as political assassins.

2 Abortion by oral methods was legal in ancient Greece. The oath cautions only against the use of pessaries

as a potential source of lethal infection.

3 The oath does not disavow surgery, merely asks the physician to cede to others with expertise.

_OHCM_10e.indb 1 _OHCM_10e.indb 1 02052017 19:06 02052017 19:062

Thinking about medicine

Medical care

Advice for doctors

· Do not blame the sick for being sick.

· Seek to discover your patient’s wishes and comply with them.

· Learn.

·Work for your patients, not your consultant.

· Respect opinions.

· Treat a patient, not a disease.

· Admit a person, not a diagnosis.

· Spend time with the bereaved; help them to shed tears.

· Give the patient (and yourself) time: for questions, to re? ect, and to allow healing.

· Give patients the bene? t of the doubt.

· Be optimistic.

· Be kind to yourself: you are not an inexhaustible resource.

· Question your conscience.

· Tell the truth.

· Recognize that the scienti? c approach may be ? nite, but experience and empathy

are limitless.

The National Health Service

‘The resources of medical skill and the apparatus of healing shall be placed at

the disposal of the patient, without charge, when he or she needs them; that

medical treatment and care should be a communal responsibility, that they

should be made available to rich and poor alike in accordance with medical need

and by no other criteria...Society becomes more wholesome, more serene, and

spiritually healthier, if it knows that its citizens have at the back of their con-

sciousness the knowledge that not only themselves, but all their fellows, have ac-

cess, when ill, to the best that medical skill can provide...You can always ‘pass by

on the other side’. That may be sound economics. It could not be worse morals.’

Aneurin Bevan, In Place of Fear, 1952.

In 2014, the Commonwealth Fund presented an overview of international healthcare

systems examining ? nancing, governance, healthcare quality, ei ciency, evidence-

based practice, and innovation. In a scoring system of 11 nations across 11 catego-

ries, the NHS came ? rst overall, at less than half the cost per head spent in the USA.1

The King’s Fund debunks the myth that the NHS is unaf ordable in the modern era,2

although funding remains a political choice. Bevan prophesied, ‘The NHS will last as

long as there are folk left with the faith to ? ght for it.’ Guard it well.

Decision and intervention are the essence of action,re? ection and conjecture are the essence of thought;

the essence of medicine is combining these in the ser-

vice of others. We of er our ideals to stimulate thought

and action: like the stars, ideals are hard to reach, but

they are used for navigation. Orion (? g 1.2) is our star

of choice. His constellation is visible across the globe

so he links our readers everywhere, and he will remain

recognizable long after other constellations have dis-

torted.

Medicine and the stars

Fig 1.2 The const ellation of Orion has three superb stars: Bel-

latrix (the stetho scope’s bell), Betel geuse (B), and Rigel (R). The

three stars at the cross over (Orion’s Belt) are Alnitak, Alnilam, and

Mint a ka.

·JML and David Malin.

_OHCM_10e.indb 2 _OHCM_10e.indb 2 02052017 19:06 02052017 19:06Thinking about medicine

3

QALYS and resource rationing

‘There is a good deal of hit and miss about general medicine. It is a profession

where exact measurement is not easy and the absence of it opens the mind to

endless conjecture as to the ef? cacy of this or that form of treatment.’

Aneurin Bevan, In Place of Fear, 1952.

A QALY is a quality-adjusted life year. One year of healthy life expectancy = 1 QALY,whereas 1 year of unhealthy life expectancy is worth <1 QALY, the precise value falling

with progressively worsening quality of life. If an intervention means that you are

likely to live for 8 years in perfect health then that intervention would have a QALY

value of 8. If a new drug improves your quality of life from 0.5 to 0.7 for 25 years,then it has a QALY value of (0.7 Ω 0.5)≈25=5. Based on the price of the intervention, the

cost of 1 QALY can be calculated. Healthcare priorities can then be weighted towards

low cost QALYs. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) consid-

ers that interventions for which 1 QALY=<£30 000 are cost-ef ective. However, as a

practical application of utilitarian theory, QALYs remain open to criticism (table 1.1).

Remember that although for a clinician, time is unambiguous and quanti? able, time

experienced by patients is more like literature than science: a minute might be a

chapter, a year a single sentence.3

Table 1.1 The advantages and disadvantages of QALYs

Advantages Disadvantages

Transparent societal decision

making

Focuses on slice (disease), not pie (health)

Common unit for dif erent

interventions

Based on a value judgement that living longer is a

measure of success

Allows cost-ef ectiveness

analysis

Quality of life assessment comes from general public,not those with disease

Allows international comparison Potentially ageist—the elderly always have less ‘life

expectancy’ to gain

Focus on outcomes, not process ie care, compassion

The inverse care law, equity, and distributive justice:

The inverse care law states that the availability of good medical care varies inversely

with the need for it. This arises due to poorer quality services, barriers to service ac-

cess, and external disadvantage. By focusing on the bene? t gained from an interven-

tion, the QALY system treats everyone as equal. But is this really equality? Distributive

justice is the distribution of ‘goods’ so that those who are worst of become better

of .

In healthcare terms, this means allocation of resources to those in greatest need,regardless of QALYs.

The importance of compassion4

,5 in medicine is undisputed. It is an emotional re-

sponse to negativity or suf ering that motivates a desire to help. It is more than

‘pity’, which has connotations of inferiority; and dif erent from ‘empathy’, which is

a vicarious experience of the emotional state of another. It requires imaginative

indwelling into another’s condition. The ? ctional Jules Henri experiences a loss of

sense of the second person; another person’s despair alters his perception of the

world so that they are ‘connected in some universal, though unseen, pattern of

humanity’.

4

With compassion, the pain of another is ‘intensi? ed by the imagina-

tion and prolonged by a hundred echoes’.

5

Compassion cannot be taught; it re-

quires engagement with suf ering, cultural understanding, and a mutuality, rather

than paternalism. Adverse political, excessively mechanical, and managerial envi-

ronments discourage its expression. When compassion (what is felt) is dii cult,etiquette (what is done) must not fail: re? ection, empathy, respectfulness, atten-

tion, and manners count: ‘For I could never even have prayed for this: that you

would have pity on me and endure my agonies and stay with me and help me’.

6

Compassion

4 Sebastian Faulkes, Human Traces, 2005.

5 Milan Kundera, The Unbearable Lightness of Being, 1984.

6 Philoctetes by Sophocles 409 BC (translation Phillips and Clay, 2003).

_OHCM_10e.indb 3 _OHCM_10e.indb 3 02052017 19:06 02052017 19:064

Thinking about medicine

The diagnostic puzzle

How to formulate a diagnosis

Diagnosing by recognition: For students, this is the most irritating method. You

spend an hour asking all the wrong questions, and in waltzes a doctor who names

the disease before you have even ? nished taking the pulse. This doctor has simply

recognized the illness like he recognizes an old friend (or enemy).

Diagnosing by probability: Over our clinical lives we build up a personal database

of diagnoses and associated pitfalls. We unconsciously run each new ‘case’ through

this continuously developing probabilistic algorithm with increasing speed and ef-

fortlessness.

Diagnosing by reasoning: Like Sherlock Holmes, we must exclude each dif erential,and the diagnosis is what remains. This is dependent on the quality of the dif erential

and presupposes methods for absolutely excluding diseases. All tests are statistical

rather than absolute (5% of the population lie outside the ‘normal’ range), which is

why this method remains, like Sherlock Holmes, ? ctional at best.

Diagnosing by watching and waiting: The dangers and expense of exhaustive tests

may be obviated by the skilful use of time.

Diagnosing by selective doubting: Diagnosis relies on clinical signs and investiga-

tive tests. Yet there are no hard signs or perfect tests. When diagnosis is dii cult, try

doubting the signs, then doubting the tests. But the game of medicine is unplayable

if you doubt everything: so doubt selectively.

Diagnosis by iteration and reiteration: A brief history suggests looking for a few

signs, which leads to further questions and a few tests. As the process reiterates,various diagnostic possibilities crop up, leading to further questions and further

tests. And so history taking and diagnosing never end.

Heuristic pitfalls

Heuristics are the cognitive shortcuts which allow quick decision-making by focus-

ing on relevant predictors. Be aware of them so you can be vigilant of their traps.7

Representativeness: Diagnosis is driven by the ‘classic case’. Do not forget the

atypical variant.

Availability: The diseases that we remember, or treated most recently, carry more

weight in our diagnostic hierarchy. Question whether this more readily available

information is truly relevant.

Overcon? dence: Are you overestimating how much you know and how well you

know it? Probably.

Bias: The hunt for, and recall of, clinical information that ? ts with our expectations.

Can you disprove your own diagnostic hypothesis?

Illusory correlation: Associated events are presumed to be causal. But was it treat-

ment or time that cured the patient?

Consider three wise men:6

Occam’s razor: Entia non sunt multiplicanda praeter necessitatem translates as

‘entities must not be multiplied unnecessarily’. The physician should therefore seek

to achieve diagnostic parsimony and ? nd a single disease to explain all symptoms,rather than prof er two or three unrelated diagnoses.

Hickam’s dictum: Patients can have as many diagnoses as they damn well

please. Signs and symptoms may be due to more than one pathology. Indeed, a

patient is statistically more likely to have two common diagnoses than one unify-

ing rare condition.

Crabtree’s bludgeon: No set of mutually inconsistent observations can exist for

which some human intellect cannot conceive a coherent explanation however

complicated. This acts as a reminder that physicians prefer Occam to Hickam: a

unifying diagnosis is a much more pleasing thing. Con? rmation bias then ensues

as we look for supporting information to ? t with our unifying theory. Remember

to test the validity of your diagnosis, no matter how pleasing it may seem.

A razor, a dictum, and a bludgeon

_OHCM_10e.indb 4 _OHCM_10e.indb 4 02052017 19:06 02052017 19:06Thinking about medicine

5

It is always possible to be wrong8 because you remain unaware of it while it is

happening. Such error-blindness is why ‘I am wrong’ is a statement of impos-

sibility. Once you are aware that you are wrong, you are no longer wrong, and can

therefore only declare ‘I was wrong’. It is also the reason that fallibility must be

accepted as a universally human phenomenon. Conversely, certainty is the convic-

tion that we cannot be wrong because our biases and beliefs must be grounded

in fact. Certainty produces the comforting illusion that the world (and medicine)

is knowable. But be cautious of certainty for it involves a shift in perspective

inwards, towards our own convictions. This means that other people’s stories can

cease to matter to us. Certainty becomes lethal to empathy.

In order to determine how and why mistakes are made, error must be acknowl-

edged and accepted. Defensiveness is bad for progress. ‘I was wrong, but...’ is

rarely an open and honest analysis of error that will facilitate dif erent and better

action in the future. It is only with close scrutiny of mistakes that you can see the

possibility of change at the core of error. And yet, medical practice is littered with

examples of resistance to disclosure, and reward for the concealment of error.

This must change.4 Remember error blindness and protect your whistle-blowers.

Listen. It is an act of humility that acknowledges the position of others, and the

possibility of error in yourself. Knowledge persists only until it can be disproved.

Better to aspire to the aporia of Socrates:

‘At ? rst, he didn’t know...just as he doesn’t yet know the answer now either;

but he still thought he knew the answer then, and he was answering con-

· dently, as if he had knowledge. He didn’t think he was stuck before, but

now he appreciates that he is stuck...At any rate, it would seem that we’ve

increased his chances of ? nding out the truth of the matter, because now,given his lack of knowledge, he’ll be glad to undertake the investigation...Do

you think he’d have tried to enquire or learn about this matter when he thought

he knew it (even though he didn’t), until he’d become bogged down and stuck,and had come to appreciate his ignorance and to long for knowledge?’

Plato: Meno and other dialogues, 402 BC; Water? eld translation, 2005.

Being wrong

In a world in which a ‘mistake’ can be rede? ned as a ‘complication’, it is easy to

conceal error behind a veil of technical language. In 2014, a professional duty of

candour became statutory in England for incidents that cause death, severe or

moderate harm, or prolonged psychological harm. As soon as practicable, the pa-

tient must be told in person what happened, given details of further enquiries, and

of ered an apology. But this should not lead to the prof ering of a ‘tick-box’ apology

of questionable value. Be reassured that an apology is not an admission of liability.

Risks and imperfections are inherent to medicine and you have the freedom to

be sorry whenever they occur. Focus not on legislation, but on transparency and

learning. The ethics of forgiveness require a complete response in which the pa-

tient’s voice is placed at the heart of the process.9

Duty of candour

Error provides a link between medicine and the humanities. Both strive to bridge

the gap between ourselves and the world. Medicine attempts to do this in an ob-

jective manner, using disproved hypotheses (error) to progress towards a ‘truth’.

Art, however, accepts the unknown, and celebrates transience and subjectivity.

By seeing the world through someone else’s eyes, art teaches us empathy. It is at

the point where art and medicine collide that doctors can re-attach themselves

to the human race and feel those emotions that motivate or terrify our patients.

‘Unknowing’ drives medical theory, but also stories and pictures. And these are the

hallmark of our highest endeavours.

‘We all know that Art is not truth. Art is a lie that makes us realise the truth,at least the truth that is given to us to understand.’

Pablo Picasso in Picasso Speaks, 1923.

Medicine, error, and the humanities

_OHCM_10e.indb 5 _OHCM_10e.indb 5 02052017 19:06 02052017 19:066

Thinking about medicine

Bedside manner and communication skills

A good bedside manner is dynamic. It develops in the light of a patient's needs and is

grounded in honesty, humour, and humility, in the presence of human weakness. But

it is fragile: `It is unsettling to ? nd how little it takes to defeat success in medicine...

You do not imagine that a mere matter of etiquette could foil you. But the social

dimension turns out to be as essential as the scienti? c... How each interaction is

negotiated can determine whether a doctor is trusted, whether a patient is heard,whether the right diagnosis is made, the right treatment given. But in this realm

there are no perfect formulas.' (Atul Gawande, Better: A Surgeon's Notes on Performance, 2008)

A patient may not care how much you know, until they know how much you care.

Without care and trust, there can be little healing. Pre-set formulas of er, at best,a guide:

Introduce yourself every time you see a patient, giving your name and your role.

‘Introductions are about making a human connection between one human being

who is suffering and vulnerable, and another human being who wishes to help.

They begin therapeutic relationships and can instantly build trust’

Kate Granger, hellomynameis.org.uk, hellomynameis

Be friendly. Smile. Sit down. Take an interest in the patient and ask an unscripted

question. Use the patient’s name more than once.

Listen. Do not be the average physician who interrupts after 20–30 seconds.

‘Look wise, say nothing, and grunt. Speech was given to conceal thought.’

William Osler (1849–1919).

Increase the wait-time between listening and speaking. The patient may say more.

Pay attention to the non-verbal. Observe gestures, body language, and eye contact.

Be aware of your own.

Explain. Consider written or drawn explanations. When appropriate, include rela-

tives in discussions to assist in understanding and recall.

Adapt your language. An explanation in ? uent medicalese may mean nothing to

your patient.

Clarify understanding. ‘Acute’, ‘chronic’, ‘dizzy’, ‘jaundice’, ‘shock’, ‘malignant’, ‘re-

mission’: do these words have the same meaning for both you and your patient?

Be polite. It requires no talent.

‘Politeness is prudence and consequently rudeness is folly. To make enemies by

being...unnecessarily rude is as crazy as setting one’s house on ? re.’

Arthur Schopenhauer (1788–1860).

Address silent fears. Give patients a chance to raise their concerns: ‘What are you

worried this might be?’, ‘Some people worry about...., does that worry you?’

Consider the patient’s disease model. Patients may have their own explanations

for their symptoms. Acknowledge their theories and, if appropriate, make an ef ort

to explain why you think them unlikely.

‘A physician is obligated to consider more than a diseased organ, more even than

the whole man - he must view the man in his world.’

Harvey Cushing (1869–1939).

Keep the patient informed. Explain your working diagnosis and relate this to their

understanding, beliefs, and concerns. Let them know what will happen next, and the

likely timing. ‘Soon’ may mean a month to a doctor, but a day to a patient. Apologize

for any delay.

Summarize. Is there anything you have missed?

Communication, partnership, and health promotion are improved when doctors are

trained to KEPe Warm:10

· Knowing—the patient’s history, social talk.

· Encouraging—back-channelling (hmmm, aahh).

· Physically engaging—hand gestures, appropriate contact, lean in to the patient.

·Warm up—cooler, professional but supportive at the start of the consultation,making sure to avoid dominance, patronizing, and non-verbal cut-of s (ie turning

away from the patient) at the end.

_OHCM_10e.indb 6 _OHCM_10e.indb 6 02052017 19:06 02052017 19:06Thinking about medicine

7

Open questions ‘How are you?’, ‘How does it feel?’ The direction a patient

chooses of ers valuable information. ‘Tell me about the vomit.’ ‘It was dark.’

‘How dark?’ ‘Dark bits in it.’ ‘Like…?’ ‘Like bits of soil in it.’ This information is

gold, although it is not cast in the form of cof ee grounds.

Patient-centred questions Patients may have their own ideas about what

is causing their symptoms, how they impact, and what should be done. This is

ever truer as patients frequently consult Dr Google before their GP. Unless their

ideas, concerns, and expectations are elucidated, your patient may never be

fully satis? ed with you, or able to be fully involved in their own care.

Considering the whole Humans are not self-sui cient units; we are complex

relational beings, constantly reacting to events, environments, and each other.

To understand your patient’s concerns you must understand their context:

home-life, work, dreams, fears. Information from family and friends can be very

helpful for identifying triggering and exacerbating factors, and elucidating the

true underlying cause. A headache caused by anxiety is best treated not with

analgesics, but by helping the patient access support.

Silence and echoes Often the most valuable details are the most dii cult to

verbalize. Help your patients express such thoughts by giving them time: if you

interrogate a robin, he will ? y away; treelike silence may bring him to your hand.

‘Trade Secret: the best diagnosticians in medicine are not internists, but pa-

tients. If only the doctor would sit down, shut up, and listen, the patient will

eventually tell him the diagnosis.’

Oscar London, Kill as Few Patients as Possible, 1987.

Whilst powerful, silence should not be oppressive—try echoing the last words

said to encourage your patient to continue vocalizing a particular thought.

Try to avoid

Closed questions: These permit no opportunity to deny assumptions. ‘Have you

had hip pain since your fall?’ ‘Yes, doctor.’ Investigations are requested even

though the same hip pain was also present for many years before the fall!

Questions suggesting the answer: ‘Was the vomit black—like cof ee grounds?’

‘Yes, like cof ee grounds, doctor.’ The doctor’s expectations and hurry to get the

evidence into a pre-decided format have so tarnished the story as to make it

useless.

Asking questions

Shared decision-making: no decision about me, without me

Shared decision-making aims to place patients’ needs, wishes, and preferences at

the centre of clinical decision-making.

· Support patients to articulate their understanding of their condition.

· Inform patients about their condition, treatment options, bene? ts, and risk.

·Make decisions based on mutual understanding.

Consider asking not, ‘What is the matter?’ but, ‘What matters to you?’.

Consider also your tendency towards libertarian paternalism or ‘nudge’. This is when

information is given in such a way as to encourage individuals to make a particular

choice that is felt to be in their best interests, and to correct apparent ‘reasoning

failure’ in the patient. This is done by framing the information in either a positive or

negative light depending on your view and how you might wish to sway your audi-

ence. Consider the following statements made about a new drug which of ers 96%

survival compared to 94% with an older drug:

·More people survive if they take this drug.

· This new drug reduces mortality by a third.

· This new drug bene? ts only 2% of patients.

· There may be unknown side-ef ects to the new drug.

How do you choose?

_OHCM_10e.indb 7 _OHCM_10e.indb 7 02052017 19:06 02052017 19:068

Thinking about medicine

Prescribing drugs

Consult the BNF or BNF for Children or similar before giving any drug with which

you are not thoroughly familiar.

Check the patient’s allergy status and make all reasonable attempts to qualify the

reaction (table 1.2). The burden of iatrogenic hospital admission and avoidable drug-

related deaths is real. Equally, do not deny life-saving treatment based on a mild and

predictable reaction.

Check drug interactions meticulously.

Table 1.2 Drug reactions

Type of reaction Examples

True allergy Anaphylaxis: oedema, urticaria, wheeze (p794–5)

Side-ef ect All medications have side-ef ects. The most common are rash,itch, nausea, diarrhoea, lethargy, and headache

Increased ef ect

toxicity

Due to inter-individual variance. Dosage regimen normally cor-

rects for this but beware states of altered drug clearance such

as liver and renal (p305) impairment

Drug interaction Reaction due to drugs used in combination, eg azathioprine and

allopurinol, erythromycin and warfarin

Remember primum non nocere: ? rst do no harm. The more minor the illness, the

more weight this carries. Overall, doctors have a tendency to prescribe too much

rather than too little.

Consider the following when prescribing any medication:

1 The underlying pathology. Do not let the amelioration of symptoms lead to

failure of investigation and diagnosis.

2 Is this prescription according to best evidence?

3 Drug reactions. All medications come with risks, potential side-ef ects, incon-

venience to the patient, and expense.

4 Is the patient taking other medications?

5 Alternatives to medication. Does the patient really need or want medication?

Are you giving medication out of a sense of needing to do something, or because

you genuinely feel it will help the patient? Is it more appropriate to of er infor-

mation, reassurance, or lifestyle modi? cation?

6 Is there a risk of overdose or addiction?

7 Can you assist the patient? Once per day is better than four times. How easy is it

to open the bottle? Is there an intervention that can help with medicine manage-

ment, eg a multi-compartment compliance aid, patient counselling, an IT solution

such as a smartphone app?

8 Future planning. How are you going to decide whether the medication has

worked? What are the indications to continue, stop, or change the prescribed

regimen?

Pain is often seen as an unequivocally bad thing, and certainly many patients

dream of a life without pain. However, without pain we are vulnerable to ourselves

and our behaviours, and risk ignorance of underlying conditions.

While most children quickly learn not to touch boiling water as their own body

disciplines their behaviour with the punishment of pain; children born with con-

genital insensitivity to pain (CIPA) can burn themselves, break bones, and tear skin

without feeling any immediate ill ef ect. Their health is constantly at risk from

unconsciously self-mutilating behaviours and unnoticed trauma. CIPA is very rare

but examples of the human tendency for self-damage without the protective fac-

tor of pain are common. Have you ever bitten your tongue or cheek after a dental

anaesthetic? Patients with diabetic neuropathy risk osteomyelitis and arthropa-

thy in their pain-free feet.

If you receive a message of bad news, you do not solve the problem by hiding the

message. Listen to the pain as well as making the patient comfortable.

In appreciation of pain

_OHCM_10e.indb 8 _OHCM_10e.indb 8 02052017 19:06 02052017 19:06Thinking about medicine

9

The placebo ef ect

The placebo ef ect is a well-recognized phenomenon whereby patients improve af-

ter undergoing therapy that is believed by clinicians to have no direct ef ect on the

pathophysiology of their disease. The nature of the therapy (pills, rituals, massages)

matters less than whether the patient believes the therapy will help.

Examples of the placebo ef ect in modern medicine include participants in the pla-

cebo arm of a clinical trial who see dramatic improvements in their refractory illness,and patients in severe pain who assume the saline ? ush prior to their IV morphine

is opioid and reporting relief of pain before the morphine has been administered. It

is likely that much of the symptomatic relief experienced from ‘active’ medicines in

fact results from a placebo ef ect.

The complementary therapy industry has many ingenious ways of utilizing the

placebo ef ect. These can give great bene? ts to patients, often with minimal risk; but

there remains the potential for signi? cant harm, both ? nancially and by dissuading

patients from seeking necessary medical help.

Why evolution has given us bodies with a degree of self-healing ability in response

to a belief that healing will happen, and not in response to a desire for healing, is

unclear. Perhaps the belief that a solution is underway ‘snoozes’ the internal alarm

systems that are designed to tell us there is a problem, and so improve the symptoms

that result from the body’s perception of harm.

Many patients who receive therapies are unaware of their intended ef ects, thus

missing out on the narrative that may give them an expectation of improvement. Try

to ? nd time to discuss with your patients the story of how you hope treatment will

address their problems.

Compliance embodies the imbalance of power between doctor and patient: the

doctor knows best and the patient’s only responsibility is to comply with that

monopoly of medical knowledge. Devaluing of patients and ethically dubious, the

term ‘compliance’ has been relegated from modern prescribing practice. Con-

cordance is now king: a prescribing agreement that incorporates the beliefs and

wishes of the patient.

Only 50–70% of patients take medicines as prescribed to them. This leads to

concern over wasted resources and avoidable illness. Interventions that increase

concordance are promoted using the mnemonic: Educating Patients Enhances

Care Received

· Explanation: discuss the bene? ts and risks of taking and not-taking medication.

Some patients will prefer not to be treated and, if the patient has capacity and

understands the risks, such a decision should be respected.

· Problems: talk through the patient’s experience of their treatment—have they

suf ered side-ef ects which have prompted non-concordance?

· Expectations: discuss what they should expect from their treatment. This is im-

portant especially in the treatment of silent conditions where there is no symp-

tomatic bene? t, eg antihypertensive treatment.

· Capability: talk through the medication regimen with them and consider ways

to reduce its complexity.

· Reinforcement: reproduce your discussion in written form for the patient to take

home. Check how they are managing their medications when you next see them.

But remember that there is little evidence that increasing information improves

concordance. And if concordance is increased solely by the ‘education’ of the pa-

tient then it starts to look a lot like compliance.11 A truly shared agreement will

not always ‘comply’ or ‘concord’ with the prescriber. The capacity of the informed

individual to consent or not, means that in some cases, concordance looks more

like informed divergence.

Compliance and concordance

_OHCM_10e.indb 9 _OHCM_10e.indb 9 02052017 19:06 02052017 19:0610

Thinking about medicine

Surviving life on the wards

The ward round

· All entries on the patient record must have: date, time, the name of the clinician

leading the interaction, the clinical ? ndings and plan, your signature, printed name,and contact details. Make sure the patient details are at the top of every side of

paper. Write legibly—this may save more than the patient.

· A problem list will help you structure your thoughts and guide others.

· BODEX: Blood results, Observations, Drug chart, ECG, X-rays. Look at these. If you

think there is something of concern, make sure someone else looks at them too.

· Document what information has been given to the patient and relatives.

Handover

·Make sure you know when and where to attend.

·Make sure you understand what you need to do and why. ‘Check blood results’ or

‘Review warning score’ is not enough. Better to: ‘Check potassium in 4 hours and

discuss with a senior if it remains >6.0mmolL’ .

On call

·Write it down.

· The ABCDE approach (p779) to a sick patient is never wrong.

· Try and establish the clinical context of tasks you are asked to do. Prioritize and let

staf know when you are likely to get to them.

· Learn the national early warning score (NEWS) (p892, ? g A1).

· Smile, even when talking by phone. Be polite.

· Eat and drink, preferably with your team.

Making a referral

· Have the clinical notes, observation chart, drug chart, and investigation results to

hand. Read them before you call.

· Use SBAR: Situtation (who you are, who the patient is, the reason for the call),Background, Assessment of the patient now, Request.

· Anticipate: urine dip for the nephrologist, PR exam for the gastroenterologist.

With the going down of the sun we can momentarily cheer ourselves up by the

thought that we are one day nearer to the end of life on earth—and our respon-

sibility for the unending tide of illness that ? oods into our corridors, and seeps

into our wards and consulting rooms. Of course you may have many other quiet

satisfactions, but if not, read on and wink with us as we hear some fool telling us

that our aim should be to produce the greatest health and happiness for the great-

est number. When we hear this, we don’t expect cheering from the tattered ranks

of on-call doctors; rather, our ears detect a decimated groan, because these men

and women know that there is something at stake in on-call doctoring far more

elemental than health or happiness: namely survival.

Within the ? rst weeks, however brightly your armour shone, it will now be

smeared and spattered, if not with blood, then with the fallout from the many

decisions that were taken without sui cient care and attention. Force majeure on

the part of Nature and the exigencies of ward life have, we are suddenly stunned

to realize, taught us to be second-rate; for to insist on being ? rst-rate in all areas

is to sign a death warrant for ourselves and our patients. Don’t keep re-polishing

your armour, for perfectionism does not survive untarnished in our clinical world.

Rather, to ? ourish, furnish your mind and nourish your body. Regular food makes

midnight groans less intrusive. Drink plenty: doctors are more likely to be oliguric

than their patients. And do not voluntarily deny yourself the restorative power of

sleep, for it is our natural state, in which we were ? rst created, and we only wake

to feed our dreams.

We cannot prepare you for ? nding out that you are not at ease with the person

you are becoming, and neither would we dream of imposing a speci? c regimen of

exercise, diet, and mental ? tness. Finding out what can lead you through adversity

is the ar ......

Acute kidney injury 298

Addisonian crisis 836

Anaphylaxis 794

Aneurysm, abdominal aortic 654

intracranialextradural 78, 482

gastrointestinal 256, 820

rectal 629

variceal 257, 820

Antidotes, poisoning 842

Arrhythmias, broad complex 128, 804

narrow complex, SVT 126, 806

Asthma 810

Asystole 895

Atrial ? utter? brillation

Bacterial shock 790

Blast injury 851

Bradycardia 124

Burns 846

Cardiac arrest 894 (Fig A3)

Cardiogenic tamponade 802

Cardioversion, DC 770

Central line insertion (CVP line) 774

Cerebral oedema 830

Chest drain 766

Coma 786

Cricothyrotomy 772

Cyanosis 186–9

Cut-down 761

De? brillation 770, 894 (Fig A3)

Diabetes emergencies 832–4

Disseminated intravascular coagulopathy

(DIC) 352

Disaster, major 850

Encephalitis 824

Epilepsy, status 826

Extradural haemorrhage 482

Fluids, IV 666, 790

Haematemesis 256–7

Haemorrhage 790

Hyperthermia 790, 838

Hypoglycaemia 214, 834

Hypothermia 848

Intracranial pressure, raised 830

Ischaemic limb 656

Malaria 416

Malignant hyperpyrexia 572

Index to emergency topics

‘Don’t go so fast: we’re in a hurry!’—Talleyrand to his coachman.

Malignant hypertension 140

Meningitis 822

Meningococcaemia 822

Myocardial infarction 796

Needle pericardiocentesis 773

Neutropenic sepsis 352

Obstructive uropathy 641

Oncological emergencies 528

Opioid poisoning 842

Overdose 838–44

Pacemaker, temporary 776

Pericardiocentesis 773

Phaeochromocytoma 837

Pneumonia 816

Pneumothorax 814

Poisoning 838–44

Potassium, hyperkalaemia 674

hypokalaemia 674

Pulmonary embolism 818

Respiratory arrest 894 (Fig A3)

Respiratory failure 188

Resuscitation 894 (Fig A3)

Rheumatological emergencies 538

Shock 790

Smoke inhalation 847

Sodium, hypernatraemia 672

hyponatraemia 672

Spinal cord compression 466, 543

Status asthmaticus 810

Status epilepticus 826

Stroke 470

Superior vena cava obstruction 528

Supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) 806

Testicular torsion 652

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura

(TTP) 315

Thyroid storm 834

Transfusion reaction 349

Varices, bleeding 257, 820

Vasculitis, acute systemic 556

Venous thromboembolism, leg 656

pulmonary 818

Ventricular arrhythmias 128, 804

Ventricular failure, left 800

Ventricular ? brillation 894 (Fig A3)

Ventricular tachycardia 128, 804

_OHCM_10e.indb b _OHCM_10e.indb b 02052017 19:06 02052017 19:06Common haematology values

Haemoglobin men: 130–180gL p324

women: 115–160gL p324

Mean cell volume, MCV 76–96fL p326; p332

Platelets 150–400 ≈ 109

L p364

White cells (total) 4–11 ≈ 109

L p330

neutrophils 2.0–7.5 ≈ 109

L p330

lymphocytes 1.0–4.5 ≈ 109

L p330

eosinophils 0.04–0.4 ≈ 109

L p330

Blood gases

pH 7.35–7.45 p670

PaO2 >10.6kPa p670

PaCO2 4.7–6kPa p670

Base excess ± 2mmolL p670

UES (urea and electrolytes)

Sodium 135–145mmolL p672

Potassium 3.5–5.3mmolL p674

Creatinine 70–100μmolL p298–301

Urea 2.5–6.7mmolL p298–301

eGFR >60 p669

LFTS (liver function tests)

Bilirubin 3–17μmolL p272, p274

Alanine aminotransferase, ALT 5–35IUL p272, p274

Aspartate transaminase, AST 5–35IUL p272, p274

Alkaline phosphatase, ALP 30–130IUL

(non-pregnant adults)

p272, p274

Albumin 35–50gL p686

Cardiac enzymes

Troponin T <99th percentile of

upper reference limit:

value depends on local

assay

p119

Other biochemical values

Cholesterol <5mmolL p690

Triglycerides Fasting: 0.5–2.3mmolL p690

Amylase 0–180 IUdL p636

C-reactive protein, CRP <10mgL p686

Corrected calcium 2.12–2.60mmolL p676

Glucose, fasting 3.5–5.5mmolL p206

Thyroid stimulating hormone, TSH 0.5–4.2mUL p216

For all other reference intervals, see p750–7

_OHCM_10e.indb c _OHCM_10e.indb c 02052017 19:06 02052017 19:06OXFORD HANDBOOK OF

CLINICAL

MEDICINE

TENTH EDITION

Ian B. Wilkinson

Tim Raine

Kate Wiles

Anna Goodhart

Catriona Hall

Harriet O’Neill

3 _OHCM_10e.indb i _OHCM_10e.indb i 02052017 19:06 02052017 19:06Contents

Each chapter’s contents are detailed on its ? rst page

Prefaces to the ? rst and tenth editions iv

Acknowledgements v

Symbols and abbreviations vi

1 Thinking about medicine 0

2 History and examination 24

3 Cardiovascular medicine 92

4 Chest medicine 160

5 Endocrinology 202

6 Gastroenterology 242

7 Renal medicine 292

8 Haematology 322

9 Infectious diseases 378

10 Neurology 444

11 Oncology and palliative care 518

12 Rheumatology 538

13 Surgery 564

14 Clinical chemistry 662

15 Eponymous syndromes 694

16 Radiology 718

17 Reference intervals, etc. 750

18 Practical procedures 758

19 Emergencies 778

20 References 852

Index 868

Early warning score 892

Cardiac arrest 894

_OHCM_10e.indb iii _OHCM_10e.indb iii 02052017 19:06 02052017 19:06Preface to the tenth edition

This is the ? rst edition of the book without either of the original authors—Tony Hope

and Murray Longmore. Both have now moved on to do other things, and enjoy a

well-earned rest from authorship. In this book, I am joined by a Nephrologist, Gas-

troenterologist, and trainees destined for careers in Cardiology, Dermatology, and

General Practice. Five physicians, each with very dif erent interests and approaches,yet bringing their own knowledge, expertise, and styles. When combined with that

of our specialist and junior readers, I hope this creates a book that is greater than

the sum of its parts, yet true to the original concept and ethos of the original authors.

Life and medicine have moved on in the 30 years since the ? rst edition was published,but medicine and science are largely iterative; true novel ‘ground-breaking’ or ‘prac-

tice-changing’ discoveries are rare, to quote Isaac Newton: ‘If I have seen further, it

is by standing on the shoulders of giants’. Therefore, when we set about writing this

edition we drew inspiration from the original book and its authors; updating, adding,and clarifying, but trying to retain the unique feel and perspective that the OHCM has

provided to generations of trainees and clinicians.

IBW, 2017

We wrote this book not because we know so much, but because we know we

remember so little…the problem is not simply the quantity of information, but the

diversity of places from which it is dispensed. Trailing eagerly behind the surgeon,the student is admonished never to forget alcohol withdrawal as a cause of post-

operative confusion. The scrap of paper on which this is written spends a month

in the pocket before being lost for ever in the laundry. At dif erent times, and in

inconvenient places, a number of other causes may be presented to the student.

Not only are these causes and aphorisms never brought together, but when, as a

surgical house oi cer, the former student faces a confused patient, none is to hand.

We aim to encourage the doctor to enjoy his patients: in doing so we believe he

will prosper in the practice of medicine. For a long time now, house oi cers have

been encouraged to adopt monstrous proportions in order to straddle the diverse

pinnacles of clinical science and clinical experience. We hope that this book will

make this endeavour a little easier by moving a cumulative memory burden from

the mind into the pocket, and by removing some of the fears that are naturally felt

when starting a career in medicine, thereby freely allowing the doctor’s clinical

acumen to grow by the slow accretion of many, many days and nights.

RA Hope and JM Longmore, 1985

Preface to the ? rst edition

_OHCM_10e.indb iv _OHCM_10e.indb iv 02052017 19:06 02052017 19:06Symbols and abbreviations

..........this fact or idea is important

.......don’t dawdle!—prompt action saves lives

1 ...........reference

:......male-to-female ratio. :=2:1 means twice as

common in males

.........therefore

~ ..........approximately

–ve ......negative (+ve is positive)

........ increased or decreased

.......normal (eg serum level)

1° ........primary

2° ........secondary

..........diagnosis

........dif erential diagnosis

A:CR ......albumin to creatinine ratio (mgmmol)

A2 .........aortic component of the 2nd heart sound

Ab ......antibody

ABC ......airway, breathing, and circulation

ABG .....arterial blood gas: PaO2, PaCO2, pH, HCO3

ABPA ....allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis

ACE-i .....angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor

ACS .......acute coronary syndrome

ACTH ....adrenocorticotrophic hormone

ADH .....antidiuretic hormone

AF ........atrial ? brillation

AFB ......acid-fast bacillus

Ag .......antigen

AIDS ....acquired immunode? ciency syndrome

AKI ........acute kidney injury

ALL ......acute lymphoblastic leukaemia

ALP ......alkaline phosphatase

AMA ....antimitochondrial antibody

AMP .....adenosine monophosphate

ANA .....antinuclear antibody

ANCA ...antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody

APTT ....activated partial thromboplastin time

AR ........aortic regurgitation

ARB .....angiotensin II receptor ‘blocker’ (antagonist)

ARDS ...acute respiratory distress syndrome

ART ......antiretroviral therapy

AS ........aortic stenosis

ASD .....atrial septal defect

AST ......aspartate transaminase

ATN ......acute tubular necrosis

ATP ......adenosine triphosphate

AV ........atrioventricular

AVM .....arteriovenous malformation(s)

AXR .....abdominal X-ray (plain)

Ba ........barium

BAL ......bronchoalveolar lavage

bd .......bis die (Latin for twice a day)

BKA .....below-knee amputation

BNF ......British National Formulary

BNP ......brain natriuretic peptide

BP ........blood pressure

BPH ......benign prostatic hyperplasia

bpm ....beats per minute

ca ........cancer

CABG ...coronary artery bypass graft

cAMP ...cyclic adenosine monophosphate (AMP)

CAPD ...continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis

CCF ......congestive cardiac failure (ie left and right heart

failure)

CCU ......coronary care unit

CDT ......Clostridium dif? cile toxin

CHB ......complete heart block

CHD ......coronary heart disease

CI .........contraindications

CK ........creatine (phospho)kinase

CKD ......chronic kidney disease

CLL ......chronic lymphocytic leukaemia

CML .....chronic myeloid leukaemia

CMV .....cytomegalovirus

CNS ......central nervous system

COC ......combined oral contraceptive pill

COPD ....chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

CPAP ....continuous positive airway pressure

CPR ......cardiopulmonary resuscitation

CRP ......c-reactive protein

CSF ......cerebrospinal ? uid

CT ........computed tomography

CVA ......cerebrovascular accident

CVP ......central venous pressure

CVS ......cardiovascular system

CXR ......chest x-ray

d ..........day(s); also expressed as 7; months are 12

DC ........direct current

DIC ......disseminated intravascular coagulation

DIP ......distal interphalangeal

dL .......decilitre

DM .......diabetes mellitus

DOAC ...direct oral anticoagulant

DU ........duodenal ulcer

DV .....diarrhoea and vomiting

DVT ......deep venous thrombosis

DXT ......deep radiotherapy

EBV ......Epstein–Barr virus

ECG ......electrocardiogram

Echo ...echocardiogram

EDTA ....ethylene diamine tetra-acetic acid (anticoagulant

coating, eg in FBC bottles)

EEG ......electroencephalogram

eGFR ....estimated glomerular ? ltration rate (in mL

min1.73m2)

ELISA ...enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

EM .......electron microscope

EMG .....electromyogram

ENT ......ear, nose, and throat

ERCP ....endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography